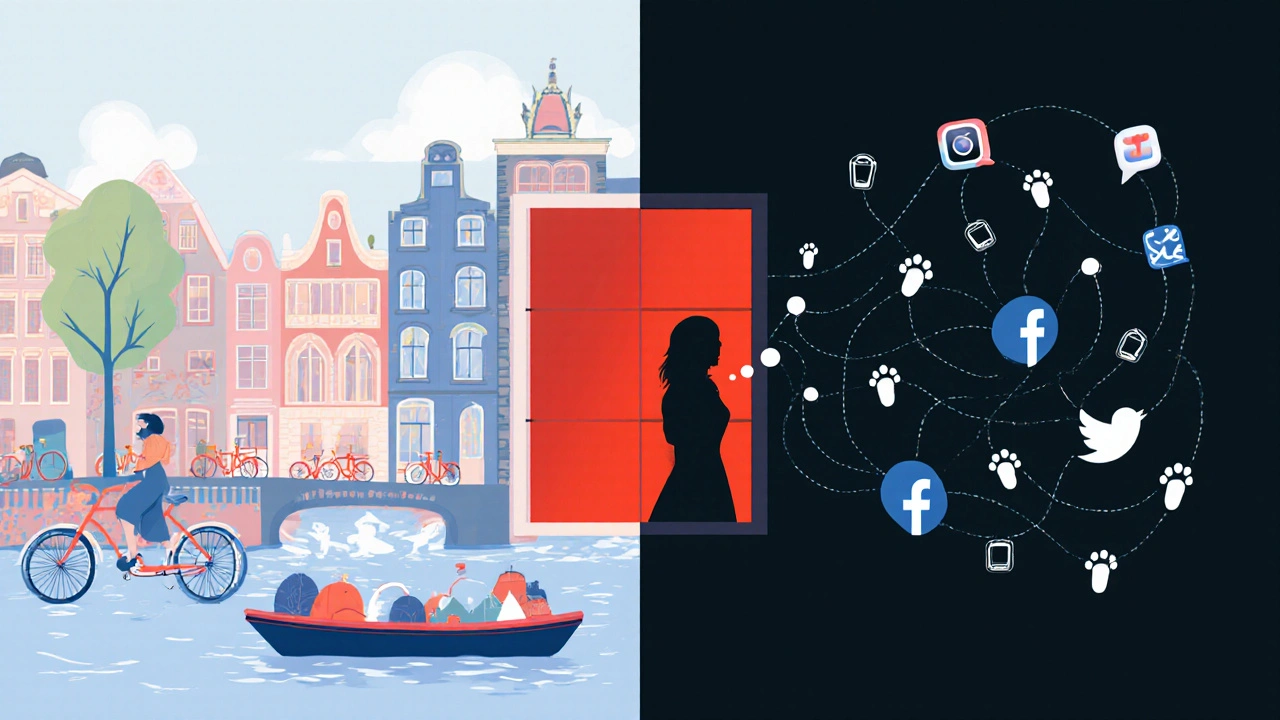

Amsterdam’s Red Light District isn’t just a place people visit-it’s a place they talk about. And that talk, whether real or imagined, has shaped how the city markets itself to millions of tourists every year. But here’s the truth most guidebooks won’t tell you: call girls aren’t part of an official marketing campaign. They never were. Yet their presence, visibility, and cultural symbolism have become unavoidable parts of Amsterdam’s global image.

How the Red Light District Became a Tourist Magnet

In the 1970s, Amsterdam legalized sex work as part of a broader policy to regulate and reduce crime. Window prostitution wasn’t created for tourism. It was created to bring sex work out of alleyways and into controlled, visible spaces where health checks, safety, and labor rights could be enforced. Over time, though, something unexpected happened: tourists started showing up.

By the 1990s, postcard vendors were selling images of women behind glass windows. Travel blogs began listing the Red Light District as a must-see. Guidebooks like Lonely Planet started describing it with the same tone as the Van Gogh Museum. The city didn’t advertise it as a tourist attraction-but it didn’t stop it either. That silence became a signal. Tourists interpreted visibility as permission.

Today, over 20 million visitors come to Amsterdam annually. Roughly 70% of them pass through or near the Red Light District. That’s not because the city ran an ad campaign. It’s because the district became a cultural shorthand for freedom, openness, and rebellion against conservative norms. The women behind the windows became symbols-not of sex, but of autonomy.

Who Are the Women Behind the Windows?

Let’s be clear: calling them ‘call girls’ is misleading. Most are not independent contractors offering private services on demand. The majority work in licensed brothels or as freelancers within a regulated system. Many are from Eastern Europe, Latin America, or Southeast Asia. Some are students. Others are single mothers. A few are entrepreneurs who built businesses around their work.

They don’t hand out flyers. They don’t appear in tourism brochures. They don’t get paid by the city. Their presence is organic, not orchestrated. Yet their visibility makes them a silent pillar of Amsterdam’s brand. The city markets itself as tolerant, liberal, and open-minded. The Red Light District is the most visible proof of that claim.

When tourists say, ‘I came to Amsterdam to see the Red Light District,’ they’re not just curious about sex. They’re curious about how a city can normalize something most others hide. That’s the real draw. Not the women themselves-but what their existence represents.

The Marketing That Never Happened

Amsterdam’s official tourism board, I Amsterdam, has never included sex work in its campaigns. Their ads show bicycles, canals, coffee shops, and museums. They promote family-friendly experiences. They even launched a ‘Respect the City’ campaign in 2019 to reduce overtourism and disrespectful behavior in the Red Light District.

But here’s the irony: the more the city tries to clean up its image, the more the Red Light District thrives as a counter-brand. Tourists don’t come because they were told to. They come because they heard about it from friends, saw it on Instagram, or read about it in a novel. The marketing is grassroots. It’s viral. It’s fueled by curiosity, shock, and myth.

Think of it this way: if you showed a tourist a photo of the Van Gogh Museum and asked, ‘Would you visit?’ they might say yes. But if you showed them a photo of a woman behind a red-lit window and asked the same question, their answer would be louder, longer, and more emotional. That’s the power of taboo.

How the City Benefits Without Direct Involvement

Amsterdam doesn’t profit directly from window prostitution. Brothel owners pay taxes. Sex workers pay income tax. The city collects VAT on drinks, food, and souvenirs sold nearby. Hotels near the Red Light District charge 30-50% more during peak season. Tourist buses stop there. Taxi drivers earn extra fares. Local shops sell postcards, keychains, and ‘I ♥ Amsterdam’ shirts with red-lit windows on them.

That’s indirect economic benefit. And it’s massive. A 2023 study by the University of Amsterdam estimated that tourism linked to the Red Light District generates over €350 million annually in direct and indirect revenue. That’s more than the city spends on public parks or bike lanes.

But here’s what’s rarely discussed: the city doesn’t have to spend a euro on advertising to get this return. All it does is allow the system to exist. That’s the cheapest marketing strategy imaginable.

The Dark Side of the Symbol

But not everyone sees this as a success story. Critics argue that reducing human beings to a tourist attraction degrades dignity. Human trafficking still exists in Amsterdam’s margins, despite strict regulations. Some women are exploited. Some are trapped. The city has cracked down on illegal operators, but the line between legal and illegal is thin.

And then there’s the behavior of tourists. In 2024, Amsterdam police reported over 12,000 incidents of harassment, photography without consent, and drunken disruption in the Red Light District. Many visitors treat the area like a zoo-peering in, snapping photos, making jokes. That’s not curiosity. It’s objectification.

The city responded with fines, increased patrols, and digital signs that say, ‘Please respect the workers. No photos.’ But signs don’t change culture. Only education can.

What’s Changing Now?

Amsterdam is slowly shifting. In 2025, the city banned new brothels in the Red Light District. Existing ones can’t expand. Tourist buses are being rerouted away from the core area. Some window spaces are being converted into small apartments or art studios.

Why? Because the city is trying to reclaim its identity. It doesn’t want to be known as the place where tourists gawk at sex workers. It wants to be known as a place where people live, work, and create.

But here’s the problem: the myth is stronger than the policy. Even if all the windows went dark tomorrow, the Red Light District would still be the first thing people Google when they plan a trip to Amsterdam. The association is too deep.

The Real Marketing Strategy

So what’s the role of call girls in Amsterdam’s tourism marketing? None-and everything.

They’re not part of the official plan. But they’re the most powerful symbol the city has. They represent freedom, tolerance, and the willingness to challenge norms. That’s what draws people. Not the act itself-but what it says about the place.

Amsterdam’s real marketing strategy isn’t about selling sex. It’s about selling the idea that this city doesn’t pretend. It doesn’t hide. It doesn’t apologize. And that’s why, despite all the controversy, it still works.

For better or worse, the women behind the windows aren’t just workers. They’re the quiet face of Amsterdam’s brand. And as long as people keep coming to see them, they’ll keep being part of the story-even if no one officially says so.